The lost Mediterranean cave-goat: A tale told by ancient DNA

Leave a reply

By Pere Bover

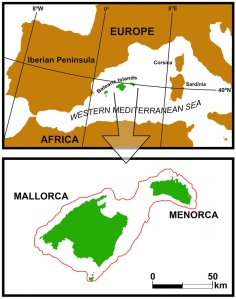

The islands of Mallorca and Menorca (Balearic Islands) in the Mediterranean Sea. The red line indicates the coast line during a maximum glacial event. Credit P. Bover

You may be wondering what a goat was doing in a cave. So was I, which is the reason I started caving around 20 years ago. In fact, these animals aren’t strictly goats, but they looked very similar (they were bovids, more closely related to sheep than goats). Sadly they are now all extinct. They intrigued me so much that the main topic of my PhD thesis was based on one of these species, Myotragus balearicus. M. balearicus is from the Balearic Islands in the Western Mediterranean. These islands, including Mallorca, with a surface of 3,640 km2 (yep! around 25 times smaller than Tasmania!!) and Menorca with 702 km2, have been isolated from the mainland since the Mediterranean basin flooding in the Late Miocene (around 5.35 Million years ago). M. balearicus survived on these two tiny islands until the first human arrival around 4,500 years ago.

For a mysterious reason these bovids liked inhabiting caves, and not just the areas surrounding the entrance, but also in deep galleries. Skeletal remains of Myotragus found in these deep galleries suggest that the animal was using caves as shelter, or even spending some time inside before dying there. Caves are known as acting as tin cans for the bones and other remains of all the animals that fall into, get trapped in, or simply live and die in them. Bones, hair, tissue and coprolites (a polite way of saying fossilized dung) can be preserved inside caves where carcasses are usually out of the reach of scavengers and weather. The remains of M. balearicus can be found in, remarkably, some of the more than 3,000 of the caves currently known and explored on these islands.

Excavation of the deposit Cova des Pas de Vallgornera in Mallorca in 2010. A remarkable amount of an ancient Myotragus species from the Early Pleistocene, M. aff. kopperi, was found in the floor of this hall. Credit: M.A. Perelló.

In just two caves from Mallorca, more than 20,000 bones of M. balearicuswere collected during several excavation campaigns. These bones have allowed scientists to study several aspects of the morphology and anatomy of the animal, and, as recently as 15 years ago, Dr. Carles Lalueza-Fox from the Institut de Biologia Evolutiva (IBE, CSIC-UPF) started obtaining DNA from several of them. His findings triggered my interest in ancient DNA and, together with Professor Alan Cooper from the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA and Dr. Joan Pons from the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Studies (IMEDEA, CSIC-UIB), we started the project MEDITADNA, funded by a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship of the 7th European Community Framework Programme. In this ongoing project we want to obtain as much genetic data as possible from Myotragus bones sourced from different Mallorcan caves, to evaluate the relationship of the fossil cave goat with other living and extinct bovids and to study population events in the past. As you can imagine, this is not an easy task. The preservation of DNA in the relatively hot and humid environments of the Mediterranean area and in old samples is usually meagre. Despite the poorly preserved DNA, we managed to get an important amount of genetic information from some of the bones excavated from seven different caves, and we are looking forward to analysing it.

Skull of Myotragus balearicus from Cova des Tancats (Menorca). Note the eye socket frontalization and the powerful jaw for chewing. This animal lived around 10,000 years ago. Credit: P. Bover.

Now, you may be wondering, why we are spending so much time on a Mediterranean, fossil goat? Why is this species so important? Well, the ancestor of this goat arrived on the Balearic Islands around 5 million of years ago where it evolved and survived in isolated conditions until relatively recent times. During this time, Myotragusunderwent a series of evolutionary changes that can be observed in the six consecutive species of the lineage. As size decreased, there was a reduction of teeth number, and eye socket frontalization. As a result of this insular evolution, the last species of the lineage, M. balearicus, was a weird animal: a dwarf (height up to 50 cm) with short legs, a big belly, small brain, frontalized eyes, and displaying a reduced number of teeth, but with really powerful mastication (chewing ability). The two islands where Myotragus lived, Mallorca and Menorca, only came into contact with each other via land bridges during cold periods (glaciations) when the sea water level dropped below the seabed between Mallorca and Menorca. During all these years, a remarkable number of severe and mild climate changes have been documented in the Mediterranean area. As an example, a global climatic change turned the Mediterranean area’s climate from tropical/subtropical to warm-temperate in the Pliocene reaching a Mediterranean climate (cooler and drier) around 3 Million years [My] ago, and, additionally, the alternation of cold periods or glaciations and warmer or interglacial periods during the last 2.4 My is also widely known. As a species you have three options for survival in response to a climate change event: 1) migrate to an area with a better climate, 2) become extinct, or 3) adapt. Myotragus was living in an extremely limited area, surrounded by water (and I’m afraid that goats are not good swimmers, or even floaters!), precluding the possibility of migration. So, it seems that Myotragus